|

"We all experience the daily, where there is "little romance," yet we continue to cast about for the sweet spot in a moment's gamble and relief. These are the poems of living, living with hope, living with crazy, living among the lost and the forsaken, always alive to experience life's essence."

—Michele Lesko, Editor, IthacaLit

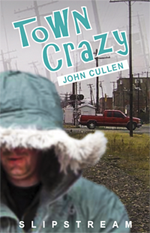

Town Crazy Copyright 2013 by John Cullen

|

John Cullen

John Cullen was raised in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York and attended school at SUNY Geneseo and BGSU. After moving to Michigan to teach at Ferris State University, he began a series of poems dramatizing his experiences of acclimating to rural West Michigan. These are the poems in this collection. Recent work has appeared in The Rathalla Review, Grist and IthacaLit.

|

|

Michigan Signs

The sign reads "Antiques, Glass, and Bait."

Behind the shelf, a pair of flintlocks crosses

a black and white photo of a bearded hunter

with ten dead wolves stretched neatly in the snow.

The shadows at his feet could be a lack of sun, or blood.

Gouged dead center by a rifle slug, a steel

plate leans against a weathered Mallard,

the caliber penciled on an index card

duct taped firmly to the decoy’s neck.

A beginner at best, I clutch my bucket

then ask the girl to net a dozen specks.

She marks her bible with a greasy feather,

then coils her hair behind her neck

while her other hand dips, netting silver fish.

She rings me up on a brand new NCR,

and when I try to make my change exact,

she points to an ashtray filled with pennies, and a sign

that tells me to take what change I need.

Then wishing me luck, the biggest in the lake,

she turns to traps and a battered red Schwinn,

a canvas belt for ammo and a stack of Reader’s Digests,

and sinks her teeth in the flesh of an apple.

Copyright ©2013 John Cullen

Annie Jillson

One December afternoon, she simply left her life

behind, her footprints marching straight

through snow and disappearing down the road.

The State police arrived hours later, following

a tip from an unknown caller who claimed

he’d found her door ajar, and then hung up

before dispatch could ask his name.

After knocks and shouts outside each window,

they wiped their feet and stepped inside.

But all they found were dishes washed and stacked,

a Herald squared on the coffee table, and a green rubber band

binding quarter wrappers from the long defunct West Trust.

Unable to think what else to do, they radioed in

to the local sheriff, who later failed to check

the attic’s trunks when he searched the house for clues.

Lake Line Power told the Herald Times Press

they’d keep her porch lights bright one month,

and knots of girls in Calley High School hallways

whispered where she’d gone and why she left—

and who the lover was who must have done her wrong.

For several weeks a neighbor fed her howling

shepherd, then paused a moment, lost in thought.

And lying in beds as if they were alone, authorities

who patrolled the lake shore counties dreamed of her

on windy nights, though her face remained a mystery.

Six months later, Mutual Trust dissolved her house

and stopped the boys who walked her porch on dares.

Now she’s a legend with pasts she couldn’t have

remembered, and a future so certain if she returned

tomorrow she’d have to walk again.

Copyright ©2013 John Cullen

|

Town Crazy

The town crazy, who once threw a water-filled condom

at a police cruiser, mumbles something

behind his beard as he stumbles along

in his fur-lined parka, pausing, loudly,

to warn a mailbox. For others

it’s summer, the heat unbearable,

and given his look of general desperation

I hope like hell he’ll keep on walking.

So I fake an interest in women’s swimwear.

Last week he caught me going to lunch

and claimed he’d found treasure in the record shop,

hundreds of albums reduced in price, ready for resale

at a solid profit, so I slipped him five and smiled good luck.

Almost a month ago, he climbed the town clock

and perched like a bird, refusing police who ordered him down.

With gas mask in hand, he cried he’d been poisoned

by the county jeep which sprays for mosquitoes.

Someone, as a joke, told the cops we were related.

They asked me, "Please, try to talk him down."

So I told him he was better wherever they weren’t,

and for whatever reason he climbed back down.

Some people say he got mixed up on drugs;

others insist he got fried in 'Nam.

I saw him, once, buy a hotdog in the park

and feed the bun to goldfish in the fountain,

all of whom he claimed he knew by name.

I keep hoping that he’ll miss me and then walk

the other way, and that somehow I’ll escape

his touch and trembling hand. But when I see his reflection,

I know I was right, and that this time he’ll need more

than simply money or a chat. I admit, at first, I wanted crazy,

like that tie with skull and crossbones near the knot,

or thoughts of a fling with a girl who hopped the bus.

But I’ve never wept for hours at a broken doll

or spoken at length with a tennis shoe.

And for the kind of moment that might become a lifetime,

I consider the possibility of refusing to turn around,

of walking away, a face in the crowd, with the weight

of fear held deep inside me. And then, as anyone

who hopes to live well, I turn the face I looked at

in the window, turn it to face the both of us.

Copyright ©2013 John Cullen

|

|